If we were to turn our gaze and meditate upon Christ crucified, Christianity would become Christian again.

There is a difference between a cross and a crucifix. A cross is a symbol. A crucifix is a story. Symbols can be used and abused to promote agendas. Think of Constantine’s famous, “In this sign, conquer.” Constantine was able to remove the cross from its story and use it as a symbol to promote the expansion of the Roman Empire. A crucifix, on the other hand, is not so easily reduced to a meaning because it tells a story. Stories do have themes that convey meaning and truth. But the truth of a story well told cannot be reduced to an abstract meaning. The truth it conveys is personal, incarnate, and practical.

When we gaze upon nothing but an empty cross, we get atonement theories. We get theological speculation as to what the cross means and what the cross does. But our four gospel accounts have little interest in atonement theology. They are telling a story of Jesus Christ crucified.

When we gaze upon Jesus on the cross, we are invited to meditate upon the meaning of what we see – but we need not be too quick to come up with an answer. What if we were to just sit before the cross, hear the story, and humbly make the confession: “This is the Son of God”?

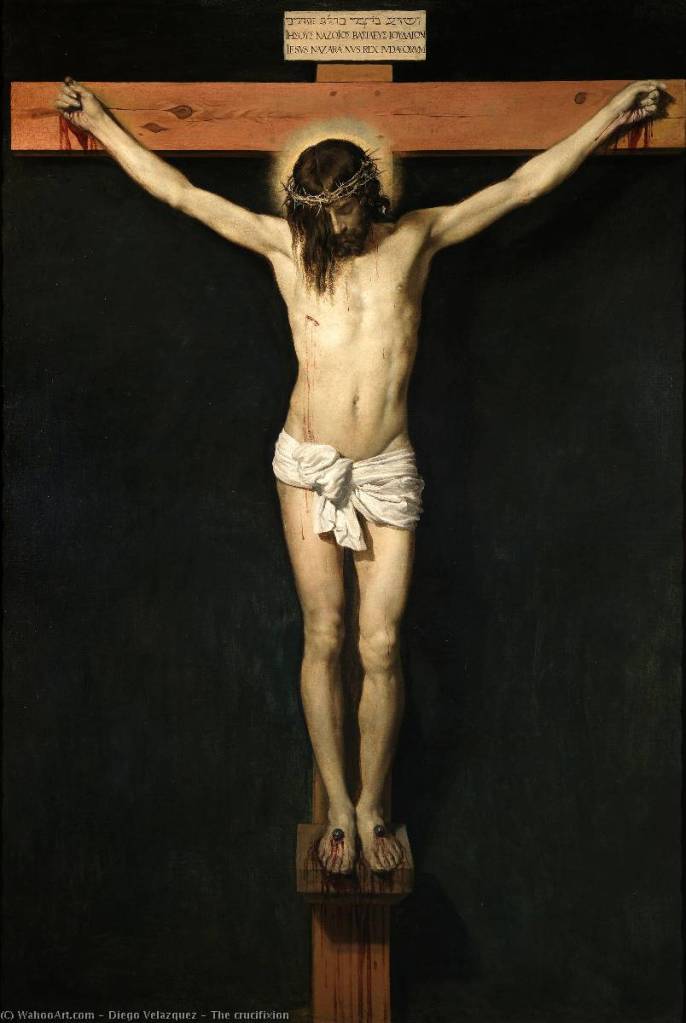

One of my favorite depictions of the crucifixion is Christ Crucified by Diego Velázquez. What I love most about this painting is its simplicity. It is comparatively undramatic. There is little blood to be seen. Jesus is not screaming in agony. Jesus is already dead and so appears peaceful. Of course, if Velázquez were going for realism, there would need to be a lot more blood. It would need to be far more graphic and grotesque. The problem with such brutal depictions of the crucifixion (like what we see in Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ) is that these make us nothing more than voyeurs of violence.

Velázquez is not interested in voyeurism. What we see in Christ Crucified is enough realism to tell the story, but enough simplicity to leave room for contemplation. We see a thin, almost completely naked dead man. Yet this dead man is, mysteriously, the only thing that brings light in the darkness.

We need to see the cross as a place of darkness. We are too quick to call the events of this day “good”. We call it “Good Friday”! But the cross cannot honestly be called “good” until the resurrection.

Crucifixion could never have been imagined in the 1st century world as good. It was a death intended to bring shame, reserved only for slaves and rebels. Even the word crux could not be used in polite company. Crosses were vulgar and profane. It was the place for the godless.

In two of our gospel accounts, the only words uttered by Jesus on the cross are the opening words of Psalm 22: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” We see the cross and hear Jesus’ cry and we see a place where God should not and cannot be. We see a place of godforsakenness, a place that God has seemingly abandoned.

Yet here is the mystery: a Roman centurion hears Jesus’ cry, does not hear an answer, then sees Jesus die. Nevertheless, the centurion confesses: “Surely this man was the Son of God.”

Do we have the imagination to gaze upon the cross and confess: This is God’s Son?

When we confess Jesus as God’s Son, the Word made flesh, then we confess that God is the God of the godforsaken. Where do we find God? We find God in the darkness, in abandonment, in brokenness, in defeat. We find God, not when we gain everything but when we lose everything. We find God, not when we live but when we die. We find God, not in success but in defeat, not in winning but in losing. God is found in the very place where we wonder if God has forsaken us.

German theologian Jürgen Moltmann put it this way: “When God becomes man in Jesus of Nazareth, he not only enters into the finitidue of man, but in his death on the cross also enters into the situation of man’s godfosrakenness. In Jesus he does not die the natural death of a finite human being, but the violent death of the criminal on the cross, the death of complete abandonment by God. The suffering in the passion of Jesus is abandonment, rejection by God, his Father. God does not become a religion, so that man participates in him by corresponding religious thoughts and feelings. God does not become a law, so that man participates in him through obedience to a law. God does not become an ideal, so that man achieves community with him through constant striving. He humbles himself and takes upon himself the eternal death of the godless and the godforsaken, so that all the godless and the godforsaken can experience communion with him.”1

It has been 2,000 years since the events of Jesus’ crucifixion took place. I am not convinced that we have yet to figure out precisely what happened on that hill outside of Jerusalem. But we continue to gaze upon the cross. We continue to proclaim Christ crucified. And we continue to confess the mystery: “This is the Son of God.”

- Jürgen Moltmann. 1993. The Crucified God : The Cross of Christ as the Foundation and Criticism of Christian Theology. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. Pg. 276 ↩︎